Cleaning the river is a must in Kumbh season but maintaining a free flow of water at optimum levels should be sacrosanct and needs to be given the importance it deserves

The current 40-day period from Makar Sankranti (January 15) to Maha Shivratri (March 4) will see the biggest ever gathering of humanity for the Maha Kumbh in Prayagraj. It is their firm belief and faith, developed over centuries and thousands of years, which will draw an estimated 12 to 14 crore pilgrims to the mela site, spread over 3,000 hectares on the banks of Holy Ganga. The management of the entire event, including crowd control and security, is a stupendous job but an even more important task would be to keep the holy waters clean and unpolluted. This is the biggest challenge.

It may not be an exaggeration to state that our work culture is such that though we excel at event management, we neglect the routine to the extent of neither taking our duties at hand seriously nor fulfilling even some of the basics. The result is that targets often get revised and dates postponed. In the past, the cleaning up of the Ganga has met almost a similar fate. It is only now, during the last few years to be precise, that some seriousness in the implementation of the action plan has become visible. However, considering the enormity of the task, the given target of 2020 appears unrealistic and in all likelihood may be pushed back. So long as we undertake the Ganga clean-up project seriously, the years and dates should not worry us, as it has to be a continuous process and not just a one-time affair.

In this context, the successful clean-up of the rivers Thames and Rhine is often cited as an exemplary model. Even if they are very small in comparison to the Ganga, there is the example of the Danube river, which flows past more than 10 countries. Let’s begin with the Thames. There was a time, of course, more than 150 years ago, when even Benjamin Disraeli compared the Thames to a “Stygian pool reeking with ineffable and unbearable horror.” Besides, there were repeated cholera outbreaks on account of its contaminated water. Much later, during the heat of the summer, the stench from the river in central London had become so unbearable that the newly-built library of the House of Commons could not be used. By 1957, the Natural History Museum in London had virtually declared Thames as biologically dead. But it took four decades of recovery and revival efforts to restore its life-giving attributes. By 1997, it had become so clean that several species of fish could often be seen to thrive in its waters.

In order to clean up Rhine in the post-war scenario, five countries, namely France, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Germany and Netherlands, formed an International Commission for the Protection of Rhine against pollution. It took stringent regulatory measures spread out over three decades to clean up the river. It is relying on that experience that recently Germany has come forward and signed up to collaborate with the Government of Uttarakhand for cleaning up the river Ganga.

On the other hand, according to a recent assessment commissioned by the Government, the Quality Council of India (QCI) came up with some startling conclusions. Even after four and a half years of the Namami Gange programme, 66 towns and cities along the river still had nullahs and drains flowing directly into the Ganga. Almost 85 per cent of the nullahs did not even have screens set up to stop garbage from entering the river. Out of the 92 towns surveyed, 72 still had old legacy dump sites on the ghats with only 19 towns having a municipal solid waste plant.

Further, according to the QCI report, the parameters for the towns were the presence of dump sites near ghats, solid waste floating on the surface, installation and maintenance of screens and presence of a municipal solid waste plant. Very few towns and only those located upstream of the river in Uttarakhand fulfilled the prescribed criteria.

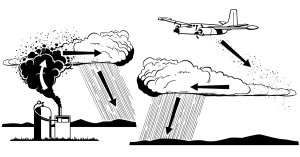

Though there are multiple factors contributing to river pollution, as may be observed, the emphasis on de-polluting the river is largely focussed on civil works, including construction of ghats besides other measures. Logically, one of the most important factors which should form the basis for cleaning up the river is the presence of adequate and optimum levels of water, as without water there can be no river.

But, for the last several years, a major part of the Ganga waters gets diverted for purposes of irrigation in the canal network. In the absence of a free flow of water and on account of several nullahs emptying into it, the self-purifying properties of the river have continued to diminish at an alarming rate. And as the glaciers feeding the Ganga recede, the quantum of water in the river is bound to diminish in times to come.

Water for irrigation is an extremely important input for the food security of the nation as well as the economy of the farming community, but at the same time it must be ensured that water, which has today become an extremely precious natural resource, should not go waste. According to available data, India has one of the highest rates of consumption of water for production per tonne of wheat, sugarcane, cotton and rice in comparison with China, the US and some other countries.

This would call for generating awareness among the farming community besides developing new technologies and adopting better agricultural practices.

As the river comes into the plains, its water gets diverted into the upper Ganga canal at Haridwar. On most occasions, except for the monsoon, the level of flow in the canal remains at a higher level than the river. Subsequently, the water from the main river gets diverted for purposes of irrigation. In case the flow of the river is maintained at higher levels, the Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) value as well as more than 50 per cent of the organic pollutants can be taken care of naturally.

From time immemorial, waters of the Ganga are considered holy due to several mythological narratives. This water has also been subjected to laboratory tests by scientists who have testified to their special qualities, some of which are attributed to the growth of medicinal plants along the river. These tests also indicate the presence of bacteriophages and some very rare minerals in traces, which kill the bacteria and impart special preservative qualities. In the absence of a free and a decreased flow, the bacteriophages and other dissolved trace minerals tend to get silted, diminishing the inherent properties of the holy water.

No doubt sewage treatment plants (STPs), sludge control, solid waste disposal, river surface cleaning, control and regulation of industrial effluents, afforestation and bio-diversity conservation remain extremely important factors in the overall plans to clean up river Ganga, but maintaining a free flow of water at optimum levels should be the fundamental basis and needs to be given the importance it deserves.